At the Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers Colorado Gold Conference last fall, I attended a ton of great panels. One of the favorite things I did was an intensive workshop on the Thursday before the main conference that covered four areas: Plotting, World Building, Character Creation and Querying.

Today, I want to talk a little bit about outlining which can be very intimidating to new and experienced writers alike. Outlining (even a little bit) is very important in my opinion because it gives the writer direction and insight into the story they’re about to create. It’s way easier to foreshadow the big traumatic event in the beginning if you know that it’s coming!

Now, there are a million ways to outline from a simple list of bullet points to a pages-long Snowflake method, but I find that many writers fall somewhere in the middle. Like, they pick and choose the elements of an outline structure that works for them and discard the things that do not serve them. I recommend doing this.

However, before you can do that, you need to know what works for you and what doesn’t. So, here are some tips along with links to the most common outlining structures for you to play with. Remember, this is your story, so write it the way you feel most comfortable. The only wrong way (except in very specific cases) is to have no plan at all. Don’t head into an unknown forest without some kind of map or you risk getting lost forever (Trust me, I know)!

Story Structure

First of all, what is a “story structure?” It is: The order of a story, in which events are organized into a beginning, middle and end. A story structure helps draw connections between “things that happen” and “things that matter.”

So, what are the basic elements of (most) stories structures? Generally, people can agree that, to be a complete story, an author needs the five elements below.

- Status Quo

- Inciting incident

- Rising Action

- All is lost

- Resolution

Most stories, regardless of the outlining method you use, will follow the same basic structure. First of all you have the Status Quo or the current state of things. This is the protagonist going about his routine life with nothing interesting happening. Think of it as your normal day at work.

Next, we have an inciting incident, which is the event that sets the story in motion. Usually this is something bad happening to the main character (they get fired, their partner breaks up with them, or aliens abduct their family). This should happen within the first few chapters to get the readers hooked and tell them what’s at stake.

Follow this with the rising action in which the character pursues their goal (they look for a new job, pursue a new love interest, try to track down the aliens). The format of this is totally dependent on the writer, but I like giving my characters more ups than downs in this section, though a few setbacks and a hefty dose of obstacles adds interest and tension.

Then we get to the all is lost moment where the protagonist believes they’ve failed so badly that nothing will ever be right. Some examples of this are they get a new job but screw up and get fired, do something bone-headed that makes their current love interest turn away, or accidentally get half their family killed. I like to put this part in the last quarter(ish) of the book right before or during the big climax action scene.

And finally, we have the resolution where the protagonist either does or doesn’t achieve their goal or realizes something else is important instead. Examples are they get their dream job, get the love interest, or save their family (maybe even find out that no one died after all!). All stories have to have some kind of resolution, though whether your readers like it (i.e. it’s happy) or don’t (i.e. sad), is up to you.

One note: Ending your story on a huge cliff-hanger (read: NOT a resolution) is bad, very bad, and please for the love of Edgar Allen Poe, just don’t. Thank you!

Now, again, this structure above is super basic, but if it’s the only outlining you ever do, just know that it’s still better than nothing because this set up creates conflict. Without conflict you have no story, merely a series of events that will struggle to keep the reader interested. And, unless you’re doing some crazy experimental shit, you won’t appeal to the readers you’re looking for.

Most popular Story Structures

So, without bias, here are some of the most popular story structures. Some you may already be familiar with (Hero’s Journey = Star Wars, amirite?) and others you may never use, but it is helpful to know them. In a sense, many of these have a lot of overlapping elements that will refer back to the basic story structure I talked about above.

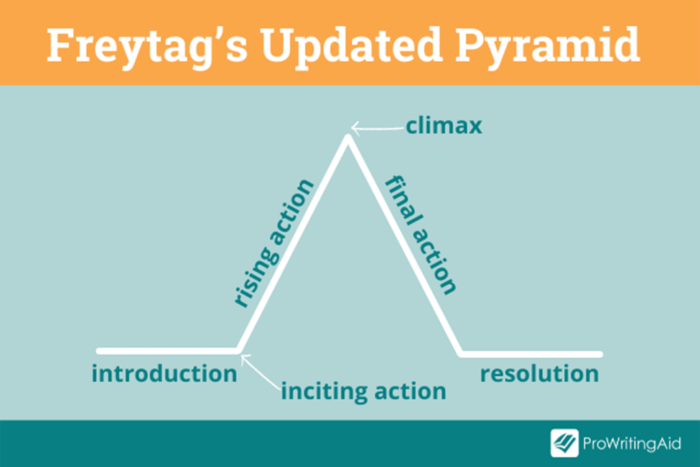

Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid is a map that highlights dramatic structure—the order of events in which the plot of a story unfolds. This is a good one for tragedies because it ends on a catastrophe. I’ve never actually used it, but I do think it looks a lot like the basic story structure above.

For more info check out this post from the Pro Writing Aid blog along with a nifty graphic (You’ll find this section full of nifty graphics).

The Hero’s Journey

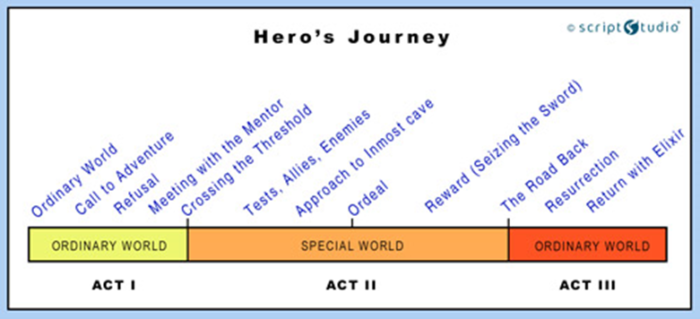

Now this is one most of us have probably heard of (see my note at the beginning of this section). This structure is based on Joseph Campbell’s concept of the monomyth. Essentially, the Hero’s Journey is a structure that appears in many stories throughout time. Some ancient examples are The Odyssey, the epic of Gilgamesh, Beowulf; the sagas of the Buddha or Prometheus or Quetzalcoatl etc. Modern(ish) examples: The Lord of the Rings, The Matrix, The Hunger Games, Interstellar etc.

Anyway, you see this all over. And while many would assert that the Hero’s Journey is overused and overplayed, well, once you understand this format you will understand why. It’s a good one and I, for one, have no problem with it if it’s done right. Though, one thing to watch out for here is playing toward too many tropes. Make sure you do your research and get some friends’ opinions if you’re not sure.

This post from Movie Outline explains its steps in detail and again, here’s another nifty graphic overlaid onto the Three Act Structure discussed below.

Three-Act Structure

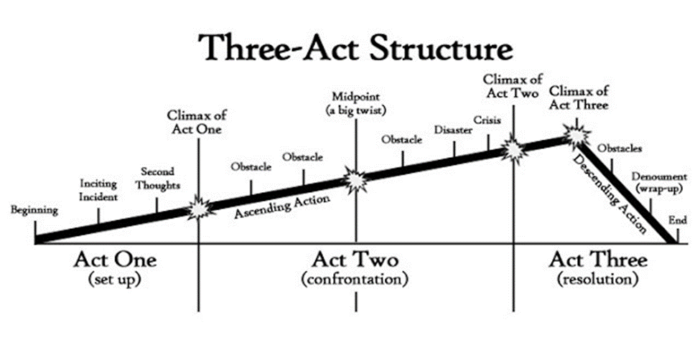

This one is the one I seem to get stuck in a lot. I don’t know why but my brain just loves this 3-part set up. Maybe it’s because I was a theatre kid and grew up with a love of plays as well as novels or maybe it’s because most of the novels I read in my formative years have this structure. I dunno, but I like it and no matter how hard I try I keep coming back to this format.

I swear I’ll break free of it someday but today is not the day. And tomorrow’s not looking good either. (Seriously, though, I am working on it with varying degrees of success).

Anyway, the basic layout of this structure is as follows (cue fun graphic):

The big thing to note in this structure is that it still follows the basic story structure, though it has mini-climaxes and twists laced in, each one getting bigger as you move forward in the story. This structure gives the protagonist lots of opportunities for obstacles and the villain lots of opportunities to inflict disaster. If you are very new to writing, this structure may be a good starting point because it can be as simple as the above or as complex as you want to make it as long as you maintain a steady upward pace in the action.

The graphic and more explanation can be found in this blog from Writer’s Edit where they discuss structure in terms of The Hunger Games (also note that Hunger Games was also listed in the Hero’s Journey so you can see how these two go together pretty well).

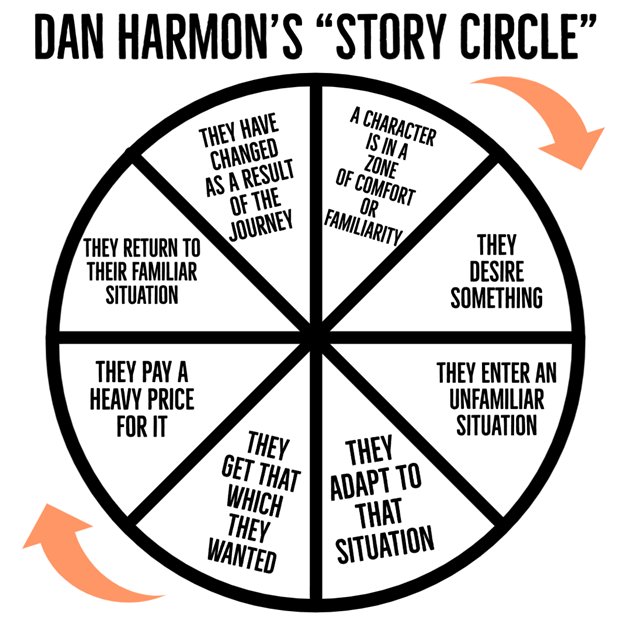

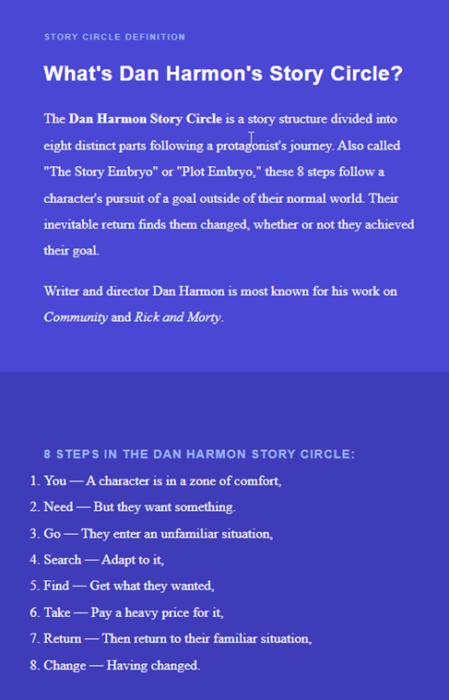

Dan Harmon’s story circle

The next one is Dan Harmon’s (yes, the co-creator of Rick and Morty) story circle, which I haven’t yet tried. To me it seems like a possibly simplified Hero’s Journey, reworked for our modern day. I like this idea a lot and have an idea to try it on a new project some day.

Since I’ve not worked much with this one, I’m just going to leave you with some nifty graphics and a link for more information from StudioBinder. Since the rainbow graphic is hard to read, I’ve provided the description as well.

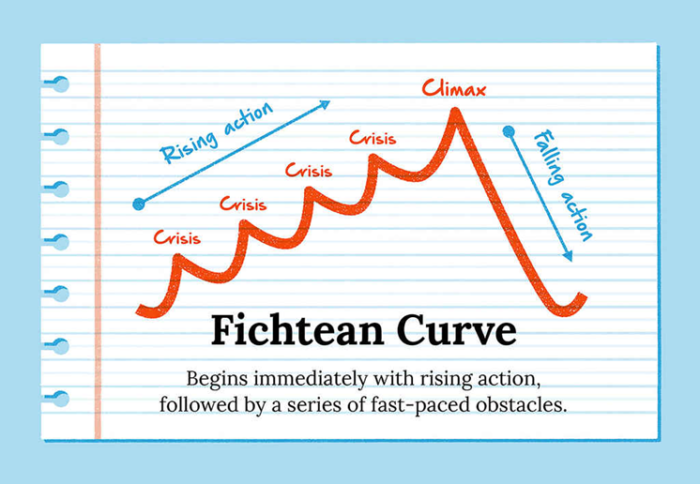

Fictean curve

This story structure is a favorite of mystery writers, of which I am not, but I will explain it as I understand it. I like to think of this one as storytelling by episodes (like a TV series) which build up to a big climax.

This structure begins immediately with the rising action completely bypassing “the ordinary world”. The inciting incident is nearly the first event and it leads into multiple crises interspersed with flashbacks (if necessary). These events do not have to be chronological in time but in order IN the novel (don’t ask me more details, mystery writers are geniuses).

In a sense, it still works up to the climax and still has a falling action/wrap up at the end, but since these books tend to be shorter than the sci-fi/fantasy stuff I write, they don’t waste words on boring worldbuilding (hah! That is a joke, please don’t hate me). Anyway, ask your favorite mystery writer if they’ve used this and how they like it. I’d love to learn more.

The below graphic and more details can be found on Reedsy.

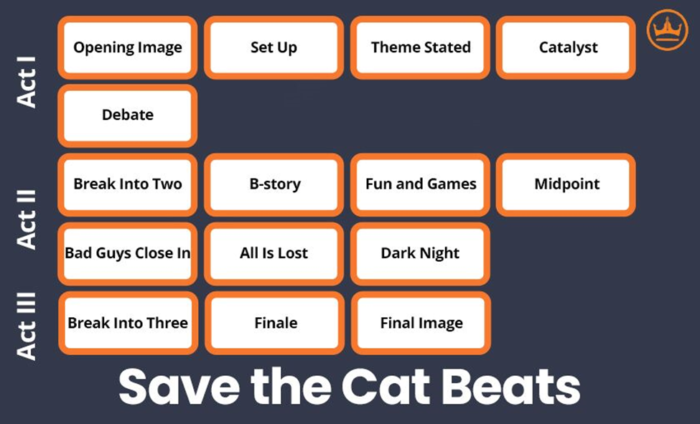

Save the Cat Beat Sheet

You may have heard of this one in terms of screenplays, but the author of this method, Blake Snyder, has also written books specifically geared toward novels, YA novels, and a bunch else. I linked his website if you want, because it’s a method that’s gotten quite big and he has lots of resources.

As I did listen to the Audiobook on the original Save the Cat, I will talk about that one which is a structure for film, though it does have some useful things for novels as well. As you’ll see in the below nifty graphic, once again this is an expansion of the Three Act Structure (OMG, maybe that’s why I can’t get the 3AS structure out of my head. It’s everywhere!)

Here he uses “catalyst” instead of “inciting incident”, “debate” instead of “rising action”, but the rest are kind pretty much in line with the Basic Story Structure. He does take into account a B-story, which is like a subplot, so that is kind of neat and he adds “fun and games” as a triumphant part that I think works specifically for movies (though let me know if you disagree!).

Also, the “dark night of the soul” is a good way to describe the protagonist’s inner feelings after the “all is lost moment” which works for novels as well. Anyway, there is a lot of discussion (or, argument) in the writer world about whether his constraints are to…um…constricting even in his novel-related research, but I feel like the ideas are solid.

In addition to his website, here’s a description of his beat sheet from Kindlepreneur where the graphic is also from.

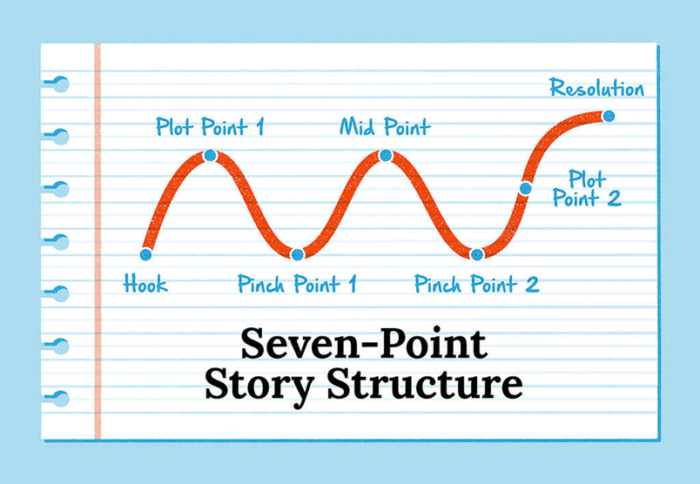

Seven-Point Story Structure

Lastly, we have the Seven Point Story Structure which is a new-ish story structure made popular by Dan Wells at the 2013 Life, the Universe, & Everything conference. He took the structure outlined in the Star Trek Roleplaying Game Narrator’s Guide and turned it into a system that he and many other authors claim to have used to build their novels.

It’s definitely an interesting structure which is one I’ve been playing with recently, so I definitely think it has some potential. Essentially, you have a series of plot points and pinch points. Plot points move the story along and pinch points are something that stymies the protagonist’s goal. Many writers use this structure by starting with the end of the story and working their way backward toward the beginning.

Here’s a graphic and description from Reedsy again, using (again!) The Hunger Games. Does this book just follow every story structure?

Anyway, this post has already gotten way too long, but I need to go to bed. Work comes too early and I’m unfortunately not getting paid to write blogs. 😉 (However, you can help change that by tipping me for my great posts through my Ko-Fi store!).

But to wrap up, here are two of my favorite story structure resources.

Since I haven’t actually gotten to outlining methods please stay tuned for Part Deux!

What is your favorite story structure? Let me know in the comments or via email! I love hearing from you all.